By Eric Noggle and Guy Stuart, Ph.D. | September 3, 2014

Last week’s post discussed how we implemented an embedded education program with VisionFund and Zoona in Zambia that leveraged touch points in an effort to improve clients’ financial capabilities. While we hope this blog series has begun to convince you that embedded education can help solve the financial capability gap, one important issue remains: where is the evidence of success? Does this approach really improve outcomes for clients and businesses?

Microfinance Opportunities (MFO) aimed to add to the knowledge base of “what works” in financial education with our evaluation of the Consumer Education for Branchless Banking (CEBB) project in Zambia.[1] The evaluation applied a mixed-methods approach with multiple data sets. We analyzed information from in-depth interviews, focus groups, knowledge surveys, and transaction data from VisionFund and Zoona’s management information systems.

The data tell a compelling story. Qualitative interviews indicated that both clients and branch staff thought the education program was having a positive impact on how clients were interacting with the branchless banking service and on their overall financial capabilities.

A consumer at Chipata Branch, for example, said:

“The training was good for me because it opened up my mind. I used to just carry on the business like I ordered goods for K50 or K60. (Then) when I sold I just used the money. When I wanted to order again I found that I was short of money and I had to borrow money to order because I had used part of my capital. But now after training I changed my system I use only profit for expenses and reinvest some profit in the business and my business has grown.”

At Lusaka Branch, a credit officer reported:

“What went well is what I would call maybe financial management or money management where (clients) really have learned to manage their income, save, planning how much they get from their business and other sources of incomes, and the importance of conventional banking as opposed to saving at home.”

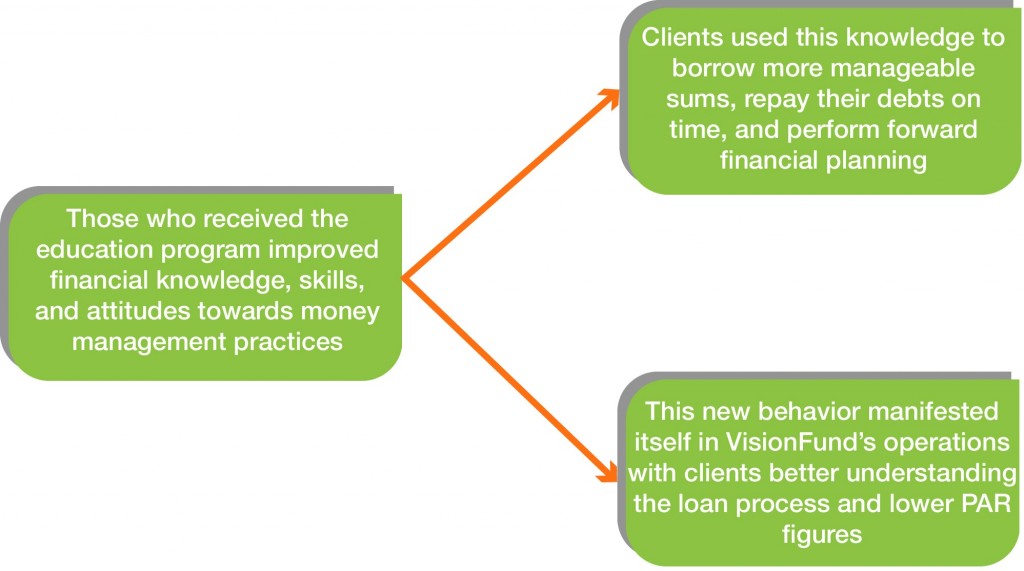

End-line survey data confirmed these insights. When compared to the baseline survey, recipients of the education program improved their score on 11 of the 12 questions assessing their knowledge, skills, or attitudes as they related to general money management and the use of the Zoona’s services. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant improvement on six of those 12 questions.

We also looked into two other effects that credit officers and branch managers reported seeing in the behavior of people who had received financial education:

- People were borrowing more manageable sums of money; and

- They were more likely to repay their debts on time.

We used a quasi-experimental design to see if this was the case. We compared transaction data from loan groups that we know received the financial education training with groups that may or may not have received the training (logistical challenges led to the uncertainty surrounding the latter set of groups). We looked at their behavior both before and after the intervention. We also took into account factors like the branch a group belonged to and their experience with the loan process. Our results showed that groups that we know received financial education training asked for an increase in their next loan that was 12 percentage points smaller than groups that did not receive the training.

While we could not look at individuals’ repayment rates, we did have access to VisionFund’s monthly portfolio-at-risk (PAR) data. We used regression analysis at the branch level with 30-Day PAR data, focusing on the branches that received financial education while controlling for branch-level changes and events that impacted the entire organization. These results were also positive. On average, the proportion of portfolio-at-risk was 7.7 percentage points lower after the intervention occurred than before. This means, for example, a branch with 10 percent portfolio-at-risk before the intervention had 2.3 percent portfolio-at-risk after the intervention, all else equal.

The qualitative and quantitative findings present a compelling argument to conclude that our embedded education program successfully improved the financial capabilities of our participants. Not only do the data complement each other, they tell a story that follows a logical progression:

This gives us good reason to believe that the embedded education model does work. Results from Zambia indicate improved financial management behavior at the individual level and that behavior change had an important bottom-line impact for the FSP VisionFund by reducing the proportion of late repayments. We believe, as we will detail in next week’s post, that this suggests that there is a business case for embedded education. Financial education that is delivered effectively, cost efficiently, and at scale has the potential to be self-sustaining for implementing parties like MFO. We’ll also share outcomes from our cases in the Philippines and India in the coming weeks.

This post is part of MFO’s new blog series, where we’ll share key learning and evidence from our current work.

[1] For examples of work that has contributed to the knowledge base of “what works” in financial education see: Keeping it Simple: Financial Literacy and Rules of Thumb, The Impact of High School Financial Education: Experimental Evidence from Brazil, and Uganda Financial Education Impact Program